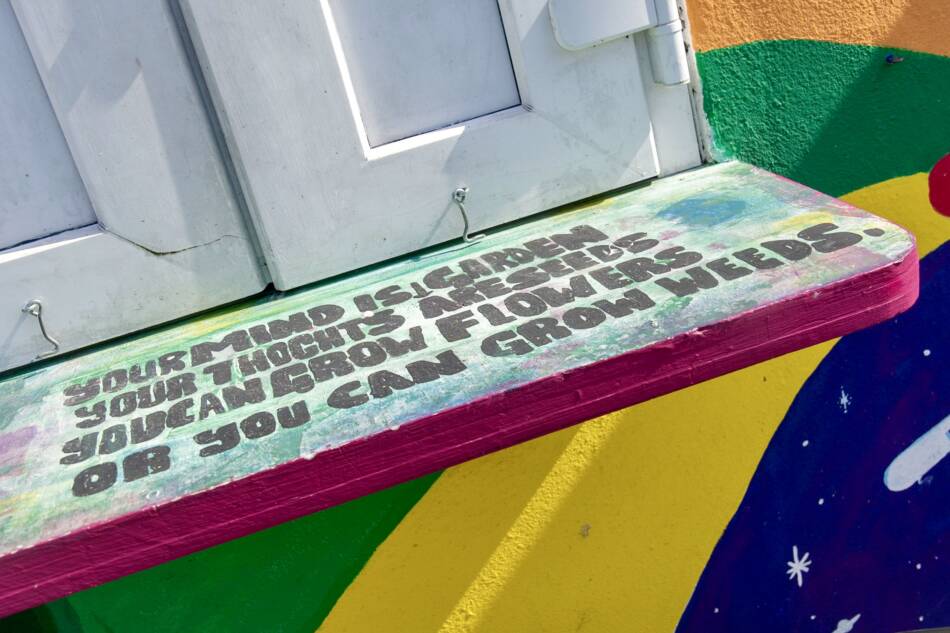

The post Thought for the day appeared first on iso200.com.

tools, technology, work

The post Thought for the day appeared first on iso200.com.

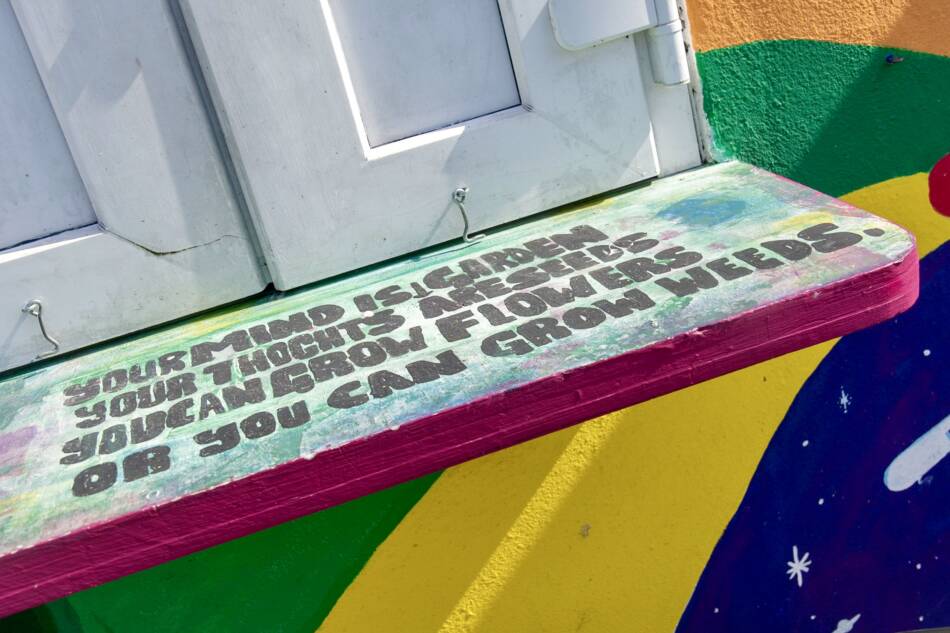

The post Shield your eyes appeared first on iso200.com.

See it on Instagram

White roof from an old fashioned buttery, Somerset, Bermuda.

Another example of why you should watch your aperture – taken at f22 – which is daft, because the resulting photo is soft (though this can be sort of fixed in post processing, why not get it right in camera?). It’s not soft through blur or shake though, but through diffraction – just because a lens has an aperture doesn’t mean you should actually use it. In this case diffraction means the lens isn’t actually capable of producing photos that are as sharp as they would be at f16.

If you’re worried about sharpness, use a tripod. Stopping down often causes more problems than it solves.

In all the talk about the engineering of cameras – pixel count, frame rates, memory cards etc. – photographers often forget that at its most fundamental level photography is about physics – it’s about light, and the manipulation of light. Your art is mediated by physics. Forget that, and your pictures will suffer.

Underneath Gibbs Hill lighthouse, Somerset, Bermuda.

This is a perfect example of why you shouldn’t use apertures below f16 – what you gain in potential depth of field you lose in shake and silly slow shutter speeds. If this had been shot at f16, ISO 200, with -1ev as it should have been, then this would have been tack sharp and worth keeping. As it is the light is fine, the clouds are good, the composition is ok… but its’ not sharp. And you will go through a phase in your photography where if it’s not sharp you don’t think twice before deleting – the sooner you get to that the better.